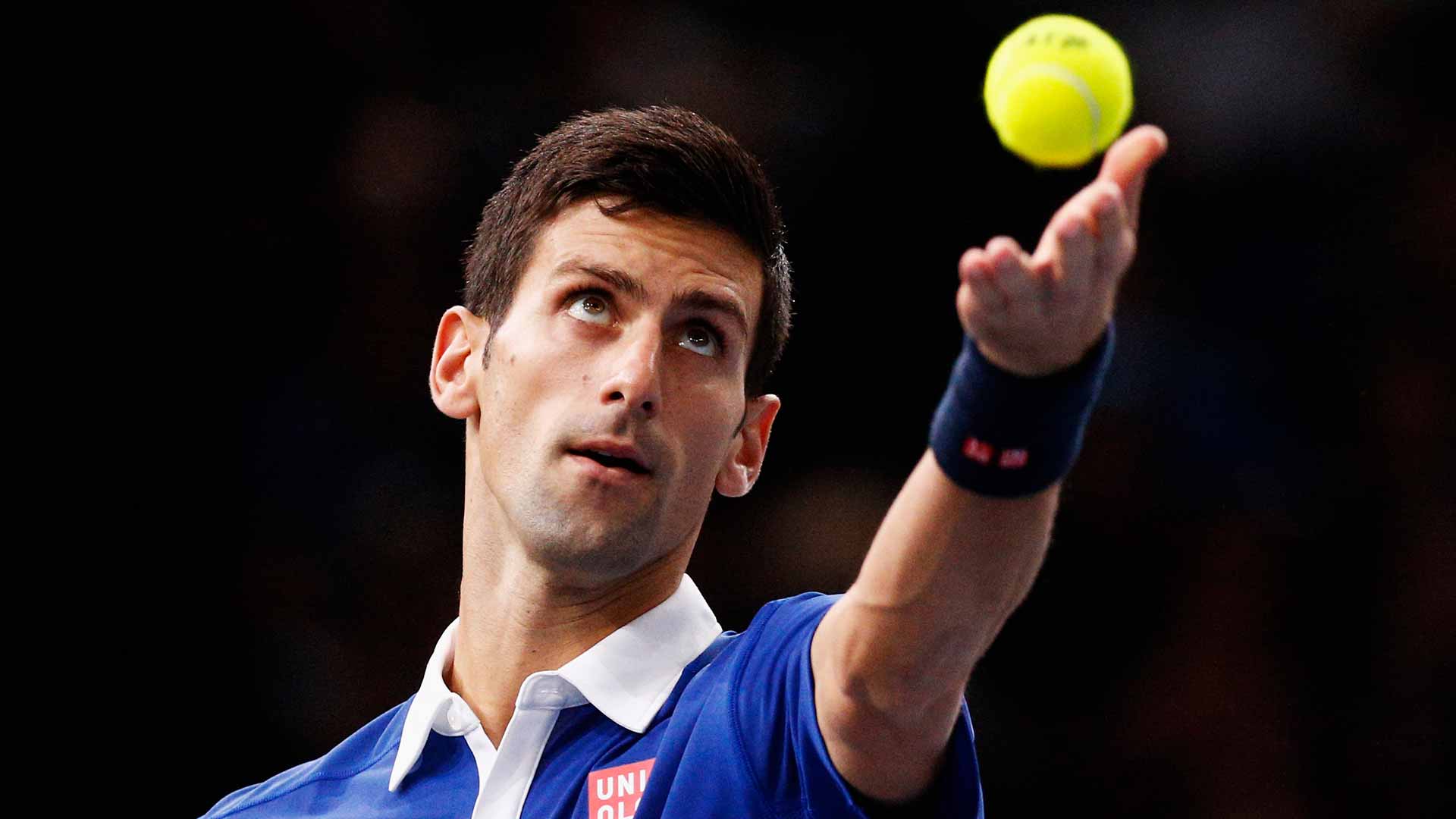

Brain Game: Djokovic Baseline Barrage Batters Murray

Is it more important to hit the ball where you want to hit it, or more important to hit it where your opponent does not want it?

That was the puzzle Andy Murray could not solve, as Novak Djokovic rolled to a 6-2, 6-4 victory in the final of the BNP Paribas Masters. What works so well for Murray against everyone else in the world is controlling the ad court with his rock-solid backhand, and then opening up angles to attack.

But not against Djokovic. Not even close.

Murray is the second best baseliner in the world in today’s game, but the gap between Djokovic and the rest of the field only seems to be getting wider. In the opening set, Djokovic completely controlled the back of the court, winning 69 per cent (27/39) of baseline points. Overall, the Serb won 67 per cent (47/70) of baseline points for the match, which is a massive advantage that allows the rest of his game to flow freely.

Djokovic’s real advantage came in mid-length rallies of five to nine shots where he stole the show, winning 68 per cent (28/41) of points, as both players tried to force their baseline patterns on the opponent. Murray actually won the longer rallies over nine shots (10-8), but with so few rallies getting this far, it simply wasn’t enough to make an impact on the final outcome.

The real key to Djokovic’s dominance was the backhand-to-backhand arm wrestle in the ad court. Murray made 25 backhand errors to Djokovic’s 11, shutting down the Brit’s strength, and making him bend to his own intentions. The quality of Murray’s backhand errors also speaks to the pressure Djokovic was putting him under in their baseline exchanges.

The number one backhand error by far from Murray was into the net with 13. Djokovic was often making contact standing closer to the baseline, which enabled better depth, and took time away from Murray’s preparation, hence the high number of net errors. Murray also made eight backhand errors long, three wide cross-court, and only one wide down the line. Murray did go to “Plan B” by coming forward to the net, winning 79 per cent (11/14) approaching, and two of three serving and volleying. The problem here for Murray is sheer volume, as dominating 17 points at the net does not come close to negating the 70 points Djokovic controlled from the back of the court.

Djokovic also applied pressure with his deep returns right down the middle, giving no angle for Murray to initially hurt him with. Murray won only 35 per cent (11/31) of his second serve points, as he often had to get out of the way of a deep Djokovic return hit right at him. The deep middle return is a hidden gem in Djokovic’s suffocating game plan. Leading into the Paris final, he had hit 49 per cent of his returns to the middle area of the court, 38 per cent wide in the ad court, and only 13 per cent wide in the deuce court. The middle of the court is a great way for Djokovic to begin the point, enabling him to then dictate from the middle of the court with his first shot after the return.

Djokovic’s forehand produced four winners, but more importantly only made eight groundstroke errors to Murray’s 19. A key pattern of play for Djokovic was to attack Murray’s forehand on the run in the deuce court, forcing Murray to make 15 of his 19 errors standing in the deuce, including seven running hard out wide near the deuce court alley. In the opening set, Murray hit 56 per cent of his forehands down the line, but 95 per cent (18/21) of those were down the line to Djokovic’s impenetrable backhand wing.

Djokovic hit 51 per cent of his forehands down the line in the opening set, and his seven inside-in forehands to Murray’s forehand primarily landed deep and close to the line in the deuce court. Beating an in-form Djokovic is a complex jigsaw puzzle of playing more to his forehand and getting to the net more than feels comfortable.

Simply hitting more winners clearly doesn’t work, as Murray hit 20 winners to the Serb’s 10 for the match, while Murray committed 34 unforced errors to Djokovic’s 12.

Djokovic makes everyone on the planet bend to his rules of engagement, and unless you have got several plans of attack mixed at exactly the right time, the Serb’s reign as the world’s best player is only getting stronger.