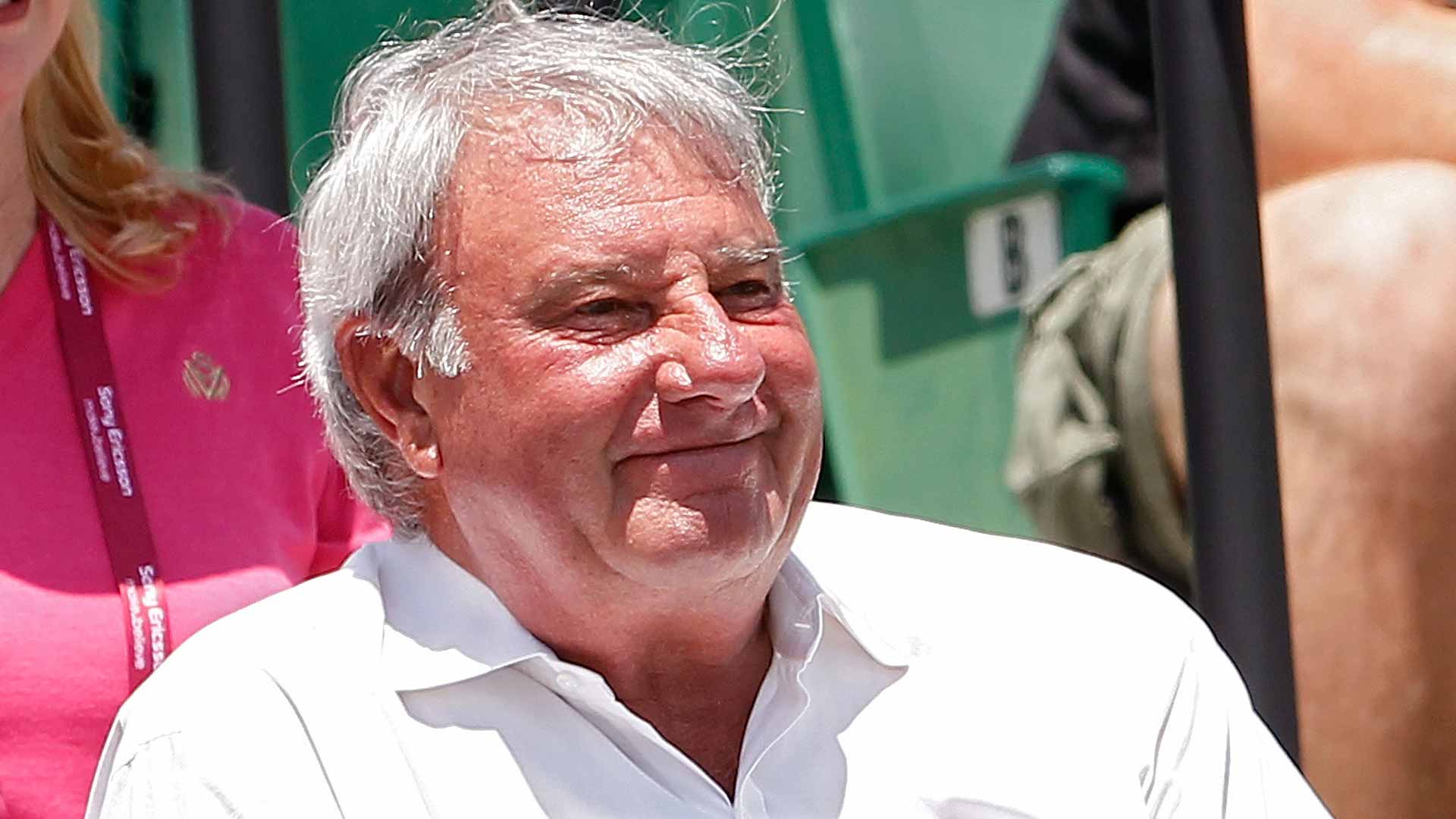

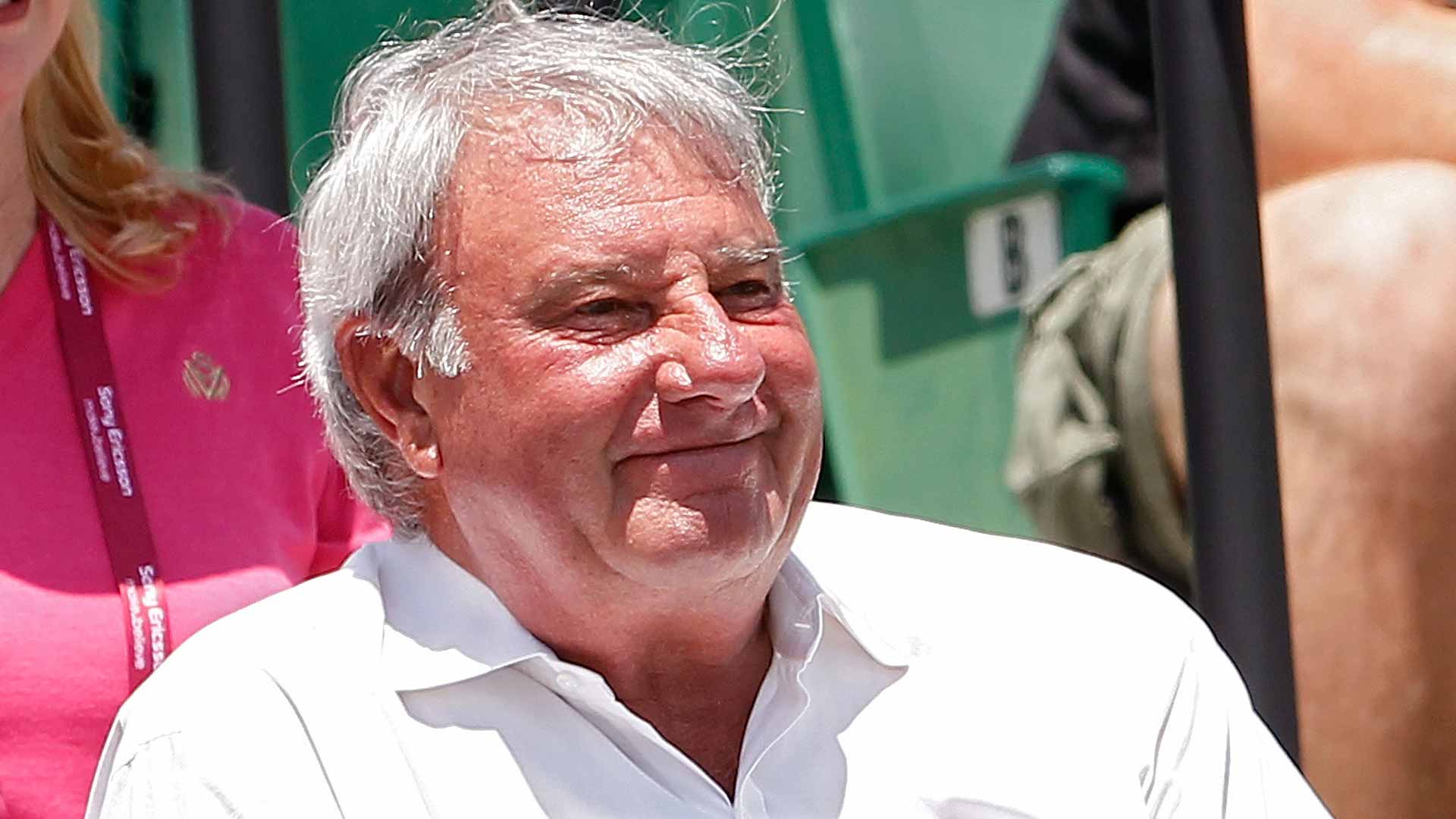

It is one of the sport’s crown jewels, first conceptualised more than 50 years ago by Earl Butch Buchholz, who realised that running a two-week tennis tournament for men and women — now named the Miami Open presented by Itau — was part of the entertainment business. When Buchholz and his younger brother, Cliff Buchholz, swept into southern Florida in 1987, after briefly holding the tournament at Delray Beach (1985) and Boca West (1986), all of their Mid-Western charm, experience and determination was needed to permanently establish a home on the beautiful island of Key Biscayne. Butch Buchholz told ATPTour.com, “I jokingly said [to my brother], ‘If things go wrong it’s your fault. If they are good, I did it.’”

Initially, amidst a five-year court battle to build a 14,000-seat stadium, the organisers — Butch, as Tournament Chairman to 2010, and Cliff, as Tournament Director to 2003 — had to deal with the second-coldest day recorded in Florida and plenty of hurricanes. Notably, the aftermath of 1992 Hurricane Andrew, one of the worst in Florida’s history, “when hundreds of fish landed on the courts” and set back their preparations for 1993, when they had to deal with a different problem. “When the stadium court was still under construction, we had to move the temporary stadium court all the way down to the end of the property,” remembers Butch Buchholz, who had initially built a $1 million 10,000-square-foot clubhouse in 1989 at Crandon Park.

“For some reason, to this day, we still don’t know why. But the court started breaking up on the final day. There was talk about the soil being bad and moisture being there. Even the heat of the day, but, for sure, it was a major crisis. At nine o’clock in the morning the court was unplayable, but when we were ready to go on air for the final [MaliVai Washington versus Pete Sampras], by a miracle, the court stuck together. It didn’t come apart and we were able to play on it. Frank Froehling, who [passed away in January 2020 and] was in the court construction business, felt that when the temporary court was built down at the end of the property, that there was probably so much moisture in there, that it was likely coming up. We also had the second-coldest day recorded in Florida in the first year, whereas the second week [of the tournament] always got hot.”

A small, but vocal section of the local community had been opposed to the development of a $20 million octagonal-shaped stadium, on the site of a former rubbish dump. The politics became fierce and the Buchholz brothers considered another venue switch. “Everyone was hopeful that we could build a stadium, but the Key Biscayne residents were worried we’d be holding rock concerts, tractor pulls and mud wrestling there,” remembers Buchholz, who had originally viewed Flamingo Park, Tropical Park and Amelia Earhart Park for Miami’s tournament site. “The people against the stadium accused us, and the county [Miami-Dade], of something we weren’t going to do. It took almost five years in court, but we won the right to build the stadium and have the tournament. But then there were all sorts of conditions, which we did not support, when the county did the contract with the prominent Matheson family. The stadium [once built] really did change the tournament.”

Buchholz’s proudest achievement, the stadium, which officially hosted its first tennis match on 11 March 1994 (one year later than planned), boasted a meditation room, hairdresser’s salon and changing rooms replete with lockers made of oak, and personalised with brass name plates. “We had the idea to invite 300,000 people to our wedding and we wanted everyone to have a good time: feed them, provide gifts [the merchandise] and enjoy their time,” says Buchholz.

“The stadium was a great office. I had the vision of the court backing, when I was playing in the 1960s. I wanted a nine-foot wall, so players didn’t have to hit a volley out of someone’s white shirt, the court was perfectly level, and television cameras were recessed into the ground. The building and the philosophy of the stadium changed everything. We gave half of the building to fans and sponsors, [and the other] half of the building to players and press. Everyone was a partner in this event. There was an area where players could sit up in dining and look out across the court. The New York Times, The Times of London were in the same seating area as a sponsor who had paid $6 million.”

Of course, the 1994 tournament didn’t go without a hitch. On the morning of the singles final, Sampras called to say he wouldn’t be able to face Andre Agassi that afternoon. Buchholz remembers telling Sampras, “If we get a doctor, and if the doctor can get you to a point where you can play, would you?’ Andre then agreed to delay the match. Pete’s doctor said, ‘If we get some IVs into him, he’ll be okay in a few hours’. I think television was due to start at 12 noon for a 1pm final start. We ended up starting around 3pm and it ended up that Pete beat him [5-7, 6-3, 6-3]. We were just happy to have a match. Andre would beat Pete the next year in a third set tie-break [3-6, 6-2, 7-6(3)], which was a great match.

“In 1996, when Goran Ivanisevic retired after three games of the final due to waking up with a stiff neck, Andre took the microphone out of my hand and told the fans, ‘This sort of thing happens…’ It’s not easy standing in front of 14,000 people saying they won’t play. At that point, I then went to the [Miami-Dade] county and asked if I could borrow their police helicopter and get Jim Courier, who was on Fisher Island [14 miles away], to play an exhibition match. I got Courier to come over and play one set against Andre, but then it poured with rain.”

By the mid 1990s, working at the Crandon Park Tennis Center had become a family affair. Buchholz had moved to Miami and was part of the fabric of the community. His son and wife worked at the tournament, which welcomed 18,000 spectators each day through the gates. His brother, Cliff, never relocated, but dealt with operations for 18 years as Tournament Director of the Miami Open presented by Itau — via title sponsorship from Lipton (1985-1999), Ericsson (2000-2001), NASDAQ-100 (2002-2006) and Sony Ericsson (2007-2014). Today the event is presented by Itaú, the largest privately owned bank in Latin America. Assisted by up to 1,200 volunteers, the tournament was initially dubbed, ‘Winter Wimbledon’ and, for the first five years, as the ‘South American Open’, playing to Miami’s strong Latin ties.

In March 1998, Chilean Marcelo Rios rose to No. 1 in the FedEx ATP Rankings after becoming the fourth of eight players to-date to complete the ‘Sunshine Double’ of BNP Paribas Open and Miami titles in the same season. Buchholz, who had also helped to create Altenis, a management company that oversaw tennis tournaments in Latin America, recalls, “What we did, we gave people coming through the gates either a Chilean flag or an American flag. That final was a bullfight, the crowds really got into it.”

It had been when Buchholz was the Executive Director of the ATP in 1981 and 1982, that he envisaged the formation of a combined tournament. He eventually agreed a 15-year contract with the ATP and WTA Tours to run the event, starting in 1985. He told ATPTour.com, “I felt that the players were the last entity to have a major event, as the golfers do with the PGA Championships at Sawgrass.” But once the tennis world changed with the ‘Parking Lot Press Conference’ at the 1988 US Open, the former player adds, “We, the ATP, owned about eight events and that really struck in every tournament’s craw. They believed the ATP would protect their own events, which was not necessarily the case, but that was the perception. When the ATP pulled off the Men’s Tennis Council [1974-1989] and started their own Tour [in 1990], Hamilton Jordan, who was the chief executive of the ATP, told me, ‘Butch, we can’t own this event. It wouldn’t look right as it’s a conflict of interest. So, if you and your brother want to take it on, we’ll increase your prize money by 40 per cent and make it a 10-day event, rather than two weeks.’ That’s how my brother and I ended up with the event.”

The 79-year-old Buchholz believes it was not just the great matches and personalities, but the attention to detail and the facilities at Crandon Park Tennis Center, which saw the Miami Open presented by Itau voted by players as the ATP Masters 1000 Tournament of the Year on six occasions (2002-06 and 2008). “The big thing for us was that the top players enjoyed coming to Miami,” says Buchholz. “We treated them very well, and the big part of our success was that our fans and sponsors could trust we could get the best players. That’s a big part of ticket and sponsorship sales. We started running it as an event and not just tennis. We had entertainment. We had a big charity event before the tournament started, also ‘Blood, Sweat and Tears’ and ‘Beach Boys’ campaigns. Food was part of the marketing. It was about attracting the locals, but also international fans to an event, and I think we were one of the first to do so. We realised that we were in the entertainment business and a lot of other tournaments followed, with men and women together being the right decision.”

Agassi, who played in Miami for the first time as a 17-year-old in 1987, was one of the event’s greatest supporters, winning a record six titles [tied with Novak Djokovic]. Upon his 19th consecutive appearance in 2005, Buchholz paid tribute. “We did a great video in his final year,” he recalls. “It was a tribute to Andre, looking back at all the 19 years. I took him into our boardroom and it was just the two of us. I showed him the video and we both cried. Our fans always remembered great matches and personalities. Pete was a big supporter, so too Chris Evert, a Florida resident. The [Rafael] Nadal-[Roger] Federer matches of 2004 and 2005, the great five-set final. The women’s matches between Monica Seles, [Steffi] Graff, [Gabriela] Sabatini and [Jennifer] Capriati. There was also Mary Joe Fernandez, who was still in high school, the Carrollton School [in Miami], and they let all the kids come and watch her play Chris Evert in the [1988] semi-finals. They literally closed the school.”

Buchholz stepped down as Tournament Chairman in March 2010, six months shy of his 70th birthday. His last duty was to present the 2010 champion Andy Roddick with the Butch Buchholz Trophy. It was a rich reward for 25 years of service to the tournament.

In 2019, the prestigious ATP Masters 1000/WTA Premier-level tournament, which had been owned by sport’s management company IMG since 2000, was held in Miami Gardens for the first time at the Hard Rock Stadium, home of the Miami Dolphins. Buchholz insists, “IMG was prepared to spend the money to bring the tournament site [at Crandon Park] back up to leading status, but wasn’t allowed to. The grounds around Key Biscayne were insufficient. [But] the Hard Rock Stadium will be great, the outer courts and the outer areas outside of the stadium are a major upgrade from Key Biscayne. I’m happy the tournament has stayed in Florida and Miami. They will have some challenging years, but it will continue to grow as the top players return to come and play. The product is very good.”

Due to the global outbreak of COVID-19, the 2020 Miami Open presented by Itau will not proceed as scheduled.