Editor’s Note: But for the COVID-19 pandemic, Wimbledon would now be underway. During the next two weeks ATPTour.com will look back on memorable matches and happenings at the grass-court Grand Slam. This story was originally published on 11 July 2019.

The serve was struck out wide to the forehand of Andre Agassi, the first volley steered into the open Ad court. Pete Sampras, not quite close enough to the net, had a split second to anticipate the exact pace and direction of the response: a flicked, improvised backhand, hit crosscourt and low over the net. Agassi, who had sprinted to his left, watched on as Sampras dove full length to pick a backhand drop volley that fell gently over the other side of the net. Agassi, now with his left arm on his waist, stared in disbelief as Sampras rose from the turf, inspecting a huge scab that had opened up on his left forearm. Having dusted himself off, the next two serves were 130 miles per hour aces from Sampras, who, in a seven-game blitz, produced an irresistible storm and carried the 1999 final at The Championships out of the hands of Agassi, who had been riding on the crest of a wave to his second Wimbledon final [1992].

From 3-3, serving at 0/40 in the first set, to the middle of the second set, memories remain vivid today, 20 years on, of one of the single greatest passages of play in the long history of the sport’s oldest championships. For Sampras, it was his perfect day. “People ask me what’s the best match I ever played? It would be that one,” the legendary American told ATPTour.com. “I played perfect grass-court tennis — moving well, returning and serving well against the best returner in the world. I was playing as well as I could and I got into the zone a bit.”

Sampras extended his seven-year record at the All England Club to 46-1, with a 6-3, 6-4, 7-5 victory over Agassi in one hour and 55 minutes on Centre Court. He’d hit 17 aces, lost just seven of his first-service points (49/56) and had made light of Agassi’s rise to No. 1 in the ATP Rankings on the back of his historic Roland Garros triumph, one month earlier. “He walked on water,” said Agassi, in the aftermath. On 4 July 1999, U.S. Independence Day, Sampras was the world’s best player.

Coming in, Sampras had lifted his first tour-level trophy for eight months at The Queen’s Club, when he beat Goran Ivanisevic, 18-year-old Lleyton Hewitt and Tim Henman in a 6-7(1), 6-4, 7-6(4) victory in the final. But walking through the Doherty Gates at the All England Club was enough for 28-year-old Sampras to know that a shot at a sixth Wimbledon crown — which would additionally equal the then all-time Grand Slam championship singles tally of Australia’s Roy Emerson (12) — was a distinct possibility.

“There is always pressure at Wimbledon, I felt like it was the Super Bowl of our sport,” says Sampras. “But quite honestly, my form didn’t really matter coming in. I had years at Wimbledon where I came in not doing well at the French and maybe not even winning at Queen’s or a sub-par year coming into Wimbledon. Everything turned around for me at Wimbledon, I felt good, Centre Court inspired me and the tournament would always turn around my year.

“Physically, mentally, it was the perfect match. Sure, you’d love to be winning and lifting trophies coming in, have confidence and let people know you’re playing well, but I didn’t feel like it was that important that I won Queen’s. I knew that once I got going to Wimbledon and through the first couple of matches, I’d be off to the races. The surface, what the place meant to me, I’d had, I always knew I’d do well.”

For all of Sampras’ success at The Championships, which would include a seventh trophy in 2000 with a final victory over Patrick Rafter, the Californian still experienced butterflies, a nervous energy heightened by the anticipation to do well. Twenty years ago, Sampras swept through the first three rounds with wins over Australia’s Scott Draper, the 1998 Queen’s Club champion, who’d beaten Boris Becker two weeks earlier, when one break in each set was enough for a 6-3, 6-4, 6-4 first-round victory; hit 17 aces in a 6-4, 6-2, 6-3 second-round encounter against Canada’s Sebastien Lareau and produced a serving masterclass against qualifier Danny Sapsford, playing his last match before taking up a coaching position with the British LTA, in a 6-3, 6-4, 7-5 victory.

Sampras remembers, “In the first rounds you’re a little nervous, trying to find your groove and rhythm. You’re maybe not as sharp and you get through a few tight sets, finding a way to break or win a tie-break. Once you get into the third or fourth round, the first weekend, you had passed the hard part and now it was time to peak and you were ready to go. The first two rounds were sometimes a little uncomfortable and you just wanted to get through them. Get it off your plate, the grass is a little slippery too. You wanted to stay on your toes, not take your foot off the pedal and win these matches handily. If I got through the first week, I knew I’d want to begin playing well and peaking. It seemed to work for me.”

Ten years away from Centre Court having a roof, the heavens opened and a four-day wait ensued for Sampras to play his fourth-round match against Canada’s Daniel Nestor — an ace-laden 6-3, 6-4, 6-2 win over 80 minutes — that stretched to the second Wednesday. “I remember it vaguely, long break can be good, but other times it feels like you’re starting the event over again,” says Sampras. “Without that roof, those years, you could play a match and then not play for three or four days. Players have it a little better today. It was a little unsettling.” At his rented house near Wimbledon village, Sampras whiled away the days with his coach, Paul Annacone — who, in 2019, is helping another American, Taylor Fritz — and his trainer, physio, masseuse, Todd Snyder, who’d worked for the men’s tour for 13 years, before joining the team in March 1995.

“It was all about tinkering with the engine, making sure your body was right,” recalls Sampras. “You were stretching and warming up on the days off: breaking a good sweat, but nothing you’re working on technically. Just taking care of your body and making sure you were ready for the next match. On my days off, I would hit for 45 minutes to an hour, I would stretch and might do a little 20-minute cool down, make sure the legs were loose, but nothing more than that. Just staying fresh. Get some good food and rest.”

With matches at the end of The Championships stacking up due to the weather, there was little Sampras could do to fine tune his game — only hope he could get through three matches in three days for Wimbledon glory.

First there was the ‘Scud’, Australia’s Mark Philippoussis, the US Open runner-up the year before, who clinched the first set 6-4, before Sampras was able to regroup prior to an untimely ending. “Early in the second set, at deuce in the third game, I hit a backhand passing shot down the line and when I landed I sort of fell awkwardly,” says Philippoussis. “That’s when I heard the click and grabbed it. I thought nothing of it until I jumped forward to return another serve and my left knee just gave way and there was a huge click that time.’ The World No. 11 knew his time was up after 52 minutes, when he heard another click on the next point.

Sampras may had dodged a bullet, trying to find his A-game after the enforced break, but 20 years on, told ATPTour.com, “Going in against Mark was an unsettling match. I didn’t feel like I was in danger of losing, as I was only one set down, but he then got injured [with a left knee injury].”

There was little time to ponder as Sampras came up against Henman, his golf partner and friend, 24 hours later in the semi-finals, for the second consecutive year. “I remember starting the match with Tim a little rusty — the match with Mark being quick,” says Sampras, who served three double faults in his opening service game and received treatment on his right thigh midway through the second set. “Playing Tim there was always tricky, not only as a very solid player, but also the crowd. I had a few different things that I had to deal with. By the end of the match, I remember I was starting to feel my game a little bit. Your heart rate goes down and you start to feel comfortable.” With a 3-6, 6-4, 6-3, 6-4 victory over the World No. 6 and British favourite, Sampras now deliberated over Agassi, one of the sport’s greatest returners.

“I had to take care of my service games and pick my spots,” remembers Sampras. “I remember using the body serve a bit with Andre that would take away the angle. On return games, it really was about not letting Andre dictate, doing something on the second serve and putting him on the defensive. I didn’t want to hang back, chipping the backhand and have him move me around. I wanted to dictate on grass and for it to be on my racquet. I didn’t want to get into long rallies or get content staying back and rallying with him. When I had my opportunity to go for it, I was going to go for it. Just set the tone early on and give Andre the impression that this final was going to be dictated by me. That was my mindset: be aggressive, even more aggressive than usual. He was a tough opponent.”

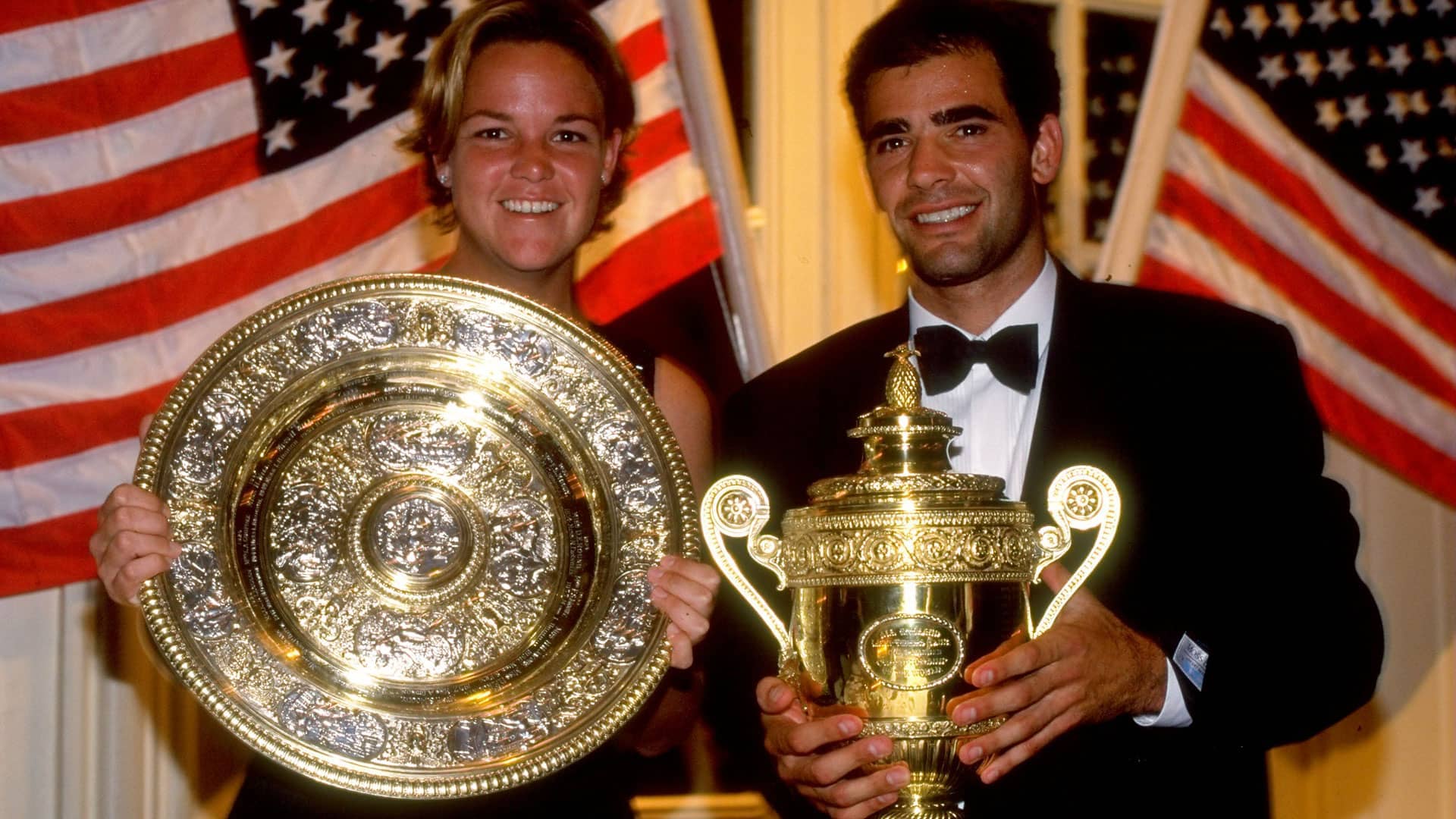

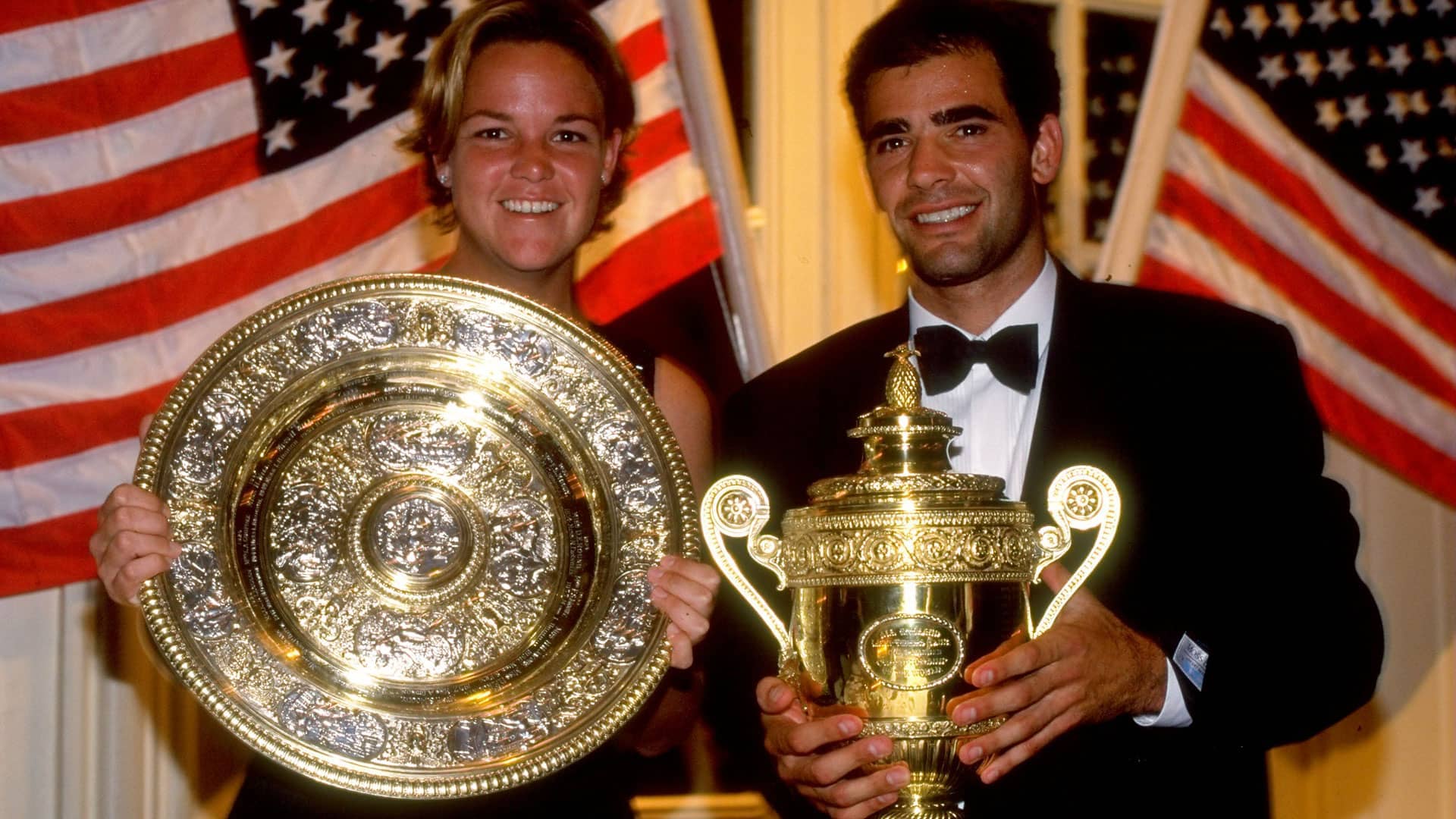

The 29-year-old Las Vegan, who had beaten Rafter 7-5, 7-6(2), 6-2 in the semi-finals, had won his first major championship for four years at Roland Garros, so the 1992 Wimbledon champion was in top form ahead of their Independence Day clash. Sampras had a 4-2 upper hand in their Grand Slam championship meetings, including victories in the 1990 and 1995 US Open finals, but baseliner Agassi had beaten Sampras at the 1995 Australian Open title match. The atmosphere was muted when they both walked out onto Centre Court on 4 July 1999, following compatriot Lindsay Davenport’s three-set win over Steffi Graf in the final Wimbledon match of the German’s trophy-laden career.

“Paul [Annacone] was always good at reminding me before I went out there of key points,” remembers Sampras, of what was discussed ahead of the first all-American Wimbledon men’s singles final since his victory over Jim Courier in 1993. “Picking the spots on my serve at the beginning of the match, when I needed to hit all the spots in the service box, as Andre was so good at picking up repetition and he’d pick you apart. It was about taking care of service games and reminding me when I was up 40/0 that I should really close out the game, rather than give him a chance. The more you hold serve, the more pressure he feels on his service games.

“In return games, I kind of knew what Andre wanted to do, but Paul always said to be aggressive and take your chances on second serve. Stay back with him, but don’t rush and wait for your opportunity, because that’s what grass-court tennis does. I loved playing baseliners, because eventually you’d get a short ball and I’d love coming up and getting to the net.”

Sampras set the tone early on in the 24th meeting of their careers, striking his backhand return — a shot that Agassi would often look to expose — with conviction and playing confidently from the back of the court. “Andre has just won the French, so he was coming in quite strong into the event,” says Sampras. “I was playing well, then I played Andre – which meant there was a little more to it than Boris [Becker] or Goran. Everything clicked, which is hard to do in a major final as there is always nerves. We got to 3-3, 0/40 in my service game, and from that moment on, and for the rest of the match, I played as well as I could.

“Andre had a chance and didn’t break me, and then I felt like I got out of a little bit of a hole. He might have gotten a bit tight, as he had those chances. It was a combination of the two that enabled me to get on that run. I let my shoulders down and just played. I had to as he was playing well, but I knew if I played well on grass, the way my game was, I felt virtually unbeatable. It was a big moment to win, more about how I played than beating Andre.”

Having recovered from 0/40 at 3-3 in the first set, Sampras broke Agassi for 5-3 with the help of a double fault, then served out the set — and en route to 3-1 in the second set, he’d won 23 of 27 points. Sampras completed the final by hitting his 16th and 17th aces. Agassi, who had won 13 straight matches to take away the World No. 1 ranking from Sampras, later admitted, “He has a knack for doing things like that. He’s a champion. He has proven that… I feel mentally and emotionally a little beat up. I didn’t feel like I was No. 1 today.”

Sampras equalled Emerson’s all-time record Grand Slam singles championship tally that day and went on to add a further two trophies — 2000 Wimbledon (d. Rafter) and the 2002 US Open (d. Agassi), which was the final match of his career — for 14 overall. Sampras says, “Wimbledon defined who I am and what I could do and play. I miss it.” Since his playing retirement in 2002, he did not return to The Championships for seven years, when he and his wife, Bridgette, took a 12-hour red-eye flight from Los Angeles to witness Roger Federer break his all-time titles’ record with a 16-14 fifth set victory over Andy Roddick in the 2009 Wimbledon final. But now, with Sampras’ youngest son, 13-year-old Ryan, developing a passion for the sport, and his elder brother, 16-year-old Christian, “asking plenty of questions and watching YouTube clips”, the American hopes to visit the All England Club in the “next year or two”.

Sampras adds, “Both my kids now know what I did and they know I was good at it. I try to give them examples of how to work hard and what it takes to be a champion. You have to work in life, nobody is going to hand it to you. That’s what tennis did to me, it gave me many life lessons and I want to teach my kids that. You’re out there on your own and you’ve got to make it happen yourself. There is no question in tennis, as an individual sport, you have to go out there and earn it.”

Goran Ivanisevic at 2001 Wimbledon” />

Goran Ivanisevic at 2001 Wimbledon” />